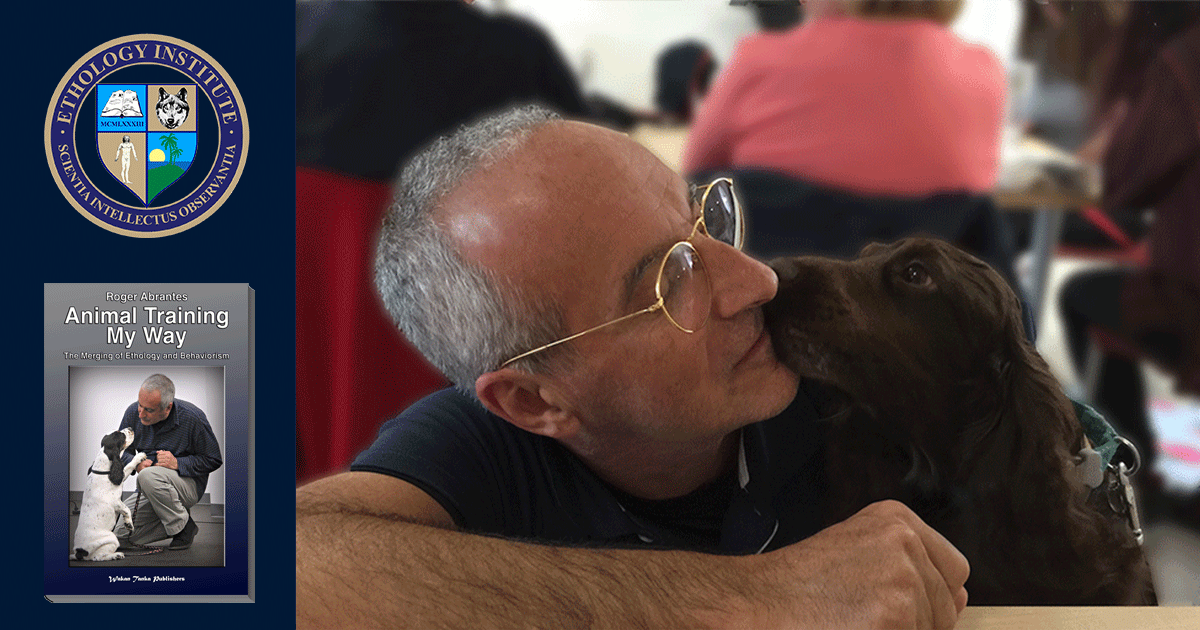

Every little drop of rain contributes to filling the beck that runs to the river that flows into the ocean. As every little piece of knowledge, you acquire, adds to improving your mindfulness, sustaining your kindness and bringing you contentment.

Knowledge, we procure by diligently, open-mindedly, unbiasedly, and critically studying, observing, listening, feeling and living. Insight is the immediate outcome of accumulated knowledge, and contentment its ultimate.

Kindness is a state of mind, an attitude toward the world, your compass on your route to reaping the benefits of knowledge. It’s an underlying quality you need to master to profit from the knowledge and insight you gain. Without it, all knowledge is to no avail, and all your best efforts will seem disjointed.

We bring you “knowledge to everyone… everywhere.” You practice it with “kindness to everyone… everywhere.” Thus, we are changing the world with knowledge and kindness—a tiny drop at the time, filling the beck that runs to the river that flows into the ocean.

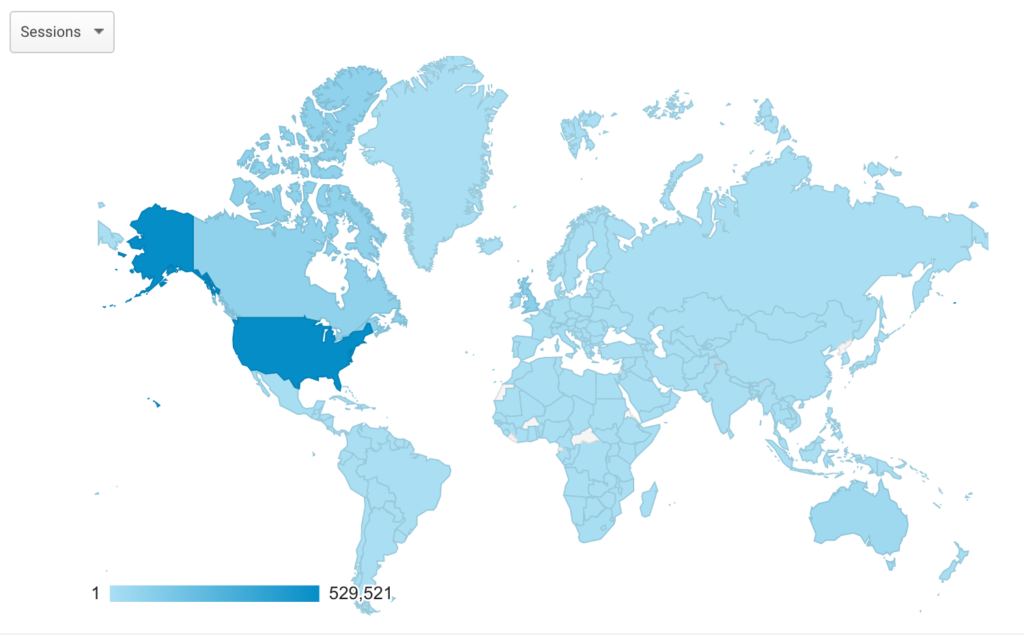

The impressive global coverage of Ethology Institute’s “knowledge to everyone… everywhere” program (from Google Analytics, March 21, 2017).

Wherever you are, be it day or night, sunny or rainy— students, tutors, admin team, and supporters—please, accept my sincere gratitude for your contribution.

Featured image: Every little drop of rain contributes to filling the beck that runs to the river that flows into the ocean.