Genes code for the traits an organism will show, physical as well as behavioral, but genes are not all. The environment of that organism also plays a crucial role in the way some of its genes will express themselves.

Genes play a large role in the appearance and behavior of organisms. Phenotypes(the appearance of the organism) are determined, in various degrees, by the genotype program (the sum of all genes) and the interaction of the organism with the environment. Some traits are more modifiable by environmental factors, others less. For example, while eye color is solely determined by the genetic coding, genes determine how tall an individual may grow, but nutritional, as well as other health factors experienced by that organism, determine the outcome. In short: the environment by itself cannot create a trait, and only a few traits are solely the product of a strict gene coding.

The same applies to behavior. Behavior is the result of the genetic coding and the effects of the environment on a particular organism. Learning is an adaptation to the environment. Behavioral genetics studies the role of genetics in animal (including human) behavior. Behavioral genetics is an interdisciplinary field, with contributions from biology, genetics, ethology, psychology, and statistics. The same basic genetic principles that apply to any phenotype also apply to behavior, but it is more difficult to identify particular genes with particular behaviors than with physical traits. The most reliable assessment of an individual’s genetic contribution to behavior is through the study of twins and half-siblings.

In small populations, like breeds with a limited number of individuals, the genetic contribution tends to be magnified because there is not enough variation. Therefore, it is very important that breeders pay special importance to lineages, keep impeccable records, test the individuals, and choose carefully, which mating system they will use. Failure to be strict may result in highly undesirable results in a few generations with the average population showing undesired traits, physical as well as behavioral.

We breed animals for many different purposes. Breeding means combining 50% of the genes of one animal (a male) to 50% of the genes of another animal (a female) and see what happens. We can never choose single genes as we wish and combine them, so we get the perfect animal, but knowing which traits are dominant, which are recessive, and being able to read pedigrees helps us.

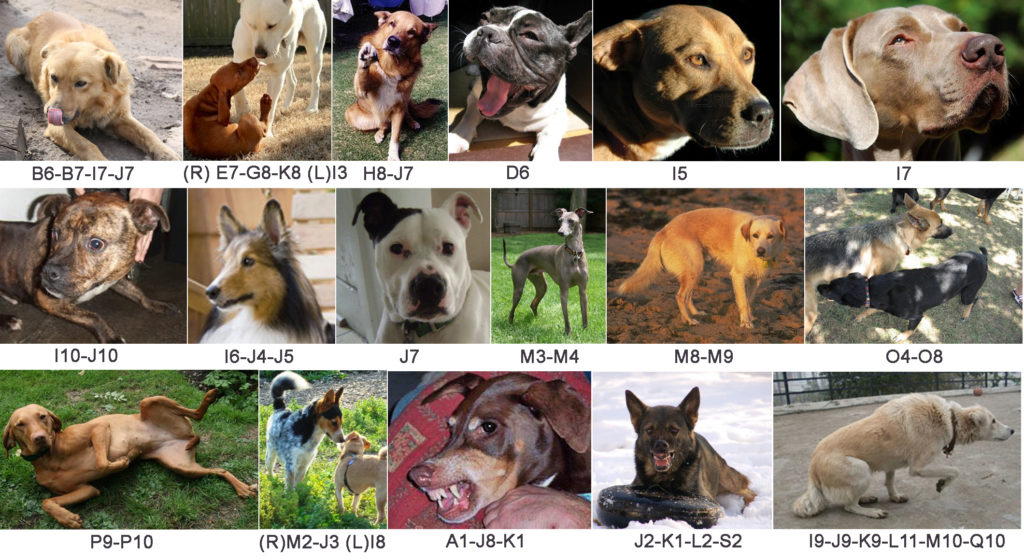

Litter mates share on average 50% common genes, but only on average. Each got at random 50% of its genes from the male (father) and 50% from the female (mother), but not necessarily the same 50% from each (Photo by TheHusky.info).

Here are some guidelines for breeding (inspired by “20 Principles of Breeding Better Dogs” by Raymond H. Oppenheimer). The objective of the following 20 principles is to help breeders strive for a healthy and fit animal in all aspects, physically as well as behaviorally.

1. The animals you select for breeding today will have an impact on the future population (unless you do not use any of their offspring to continue breeding).

2. Choose carefully the two animals you want to breed. If you only have a limited number of animals at your disposition, you will have to wait for the next generation to make any improvement. As a rule of thumb, you should expect the progeny to be better than the parents.

3. Statistical predictions may not hold true in a small number of animals (as in one litter of puppies). Statistical predictions show accuracy when applied to large populations.

4. A pedigree is a tool to help you learn the desirable and undesirable attributes that an animal is likely to exhibit or reproduce.

5. If you have a well-defined purpose for your breeding program, which you should, you will want to enhance specific attributes, but don’t forget that an animal is a whole. To emphasize one or two features of the animal, you may compromise the soundness and function of the whole organism.

6. Even though, in general, large litters indicate good health and breeding conditions, quantity does not mean quality. You produce quality through careful studies. Be patient and wait until the right breeding stock is available, evaluate what you have already produced and above all, have a breeding plan that is, at least, three generations ahead of the breeding you do today.

7. Skeletal defects are the most difficult to change.

8. Don’t bother with a good animal that cannot reproduce well. The fittest are those who survive and can pass their survival genes to the next generation.

9. Once you have approximately the animal you want, use out-crosses sparingly. For each desirable characteristic you acquire, you will get many undesirable traits that you will have to eliminate in succeeding generations.

10. Inbreedingis the fastest method to achieve desirable characteristics. It will bring forward the best and the worst of your breeding stock. You want to keep the desirable traits and eliminate the undesirable. Inbreeding will reveal hidden traits that you may consider undesirable, and want to eliminate. However, be careful, repeated inbreeding can increase the chances of offspring being affected by recessive or deleterious traits.

Adult wolves regurgitate food for the cubs to eat. Many dog mothers do the same (Photo by Humans For Wolves).

11. Once you have achieved the characteristics you want, line-breeding with sporadic outcrossing seems to be the most prudent approach.

12. Breeding does not create anything new unless you run into favorable mutations (seldom). What you get is what was there to begin with. It may have been hidden for many generations, but it was there.

13. Litter mates share on average 50% common genes, but only on average. Each one got at random 50% of its genes from the male (father) and 50% from the female (mother), but not necessarily the same 50% from each.

14. Hereditary traits are inherited equally from both parents. Do not expect to solve all of your problems in one generation.

15. If the worst animal in your last litter is no better than the worst animal in your first litter, you are not making progress.

16. If the best animal in your last litter is no better than the best animal in your first litter, you are not making progress.

17. Do not choose a breeding animal by either the best or the worst that it has produced. Evaluate the total breeding value of an animal by means of averages of as many offspring as possible.

18. Keep in mind that quality is a combination of soundness and function. It is not merely the lack of undesirable traits, but also the presence of desirable traits. It is the whole animal that counts.

19. Be objective. Don’t allow personal feelings to influence your choice of breeding stock.

20. Be realistic, but strive for excellence. Always try to get the best you can. Be careful: when we breed animals for special characteristics, physical as well as behavioral, we are playing with fire, changing the genome that natural selection created and tested throughout centuries.

Featured image: Hereditary traits are inherited equally from both parents. However, the mother will have more influence on the puppies’ behavior than the father because she spends more time with them.

Featured Course of the Week

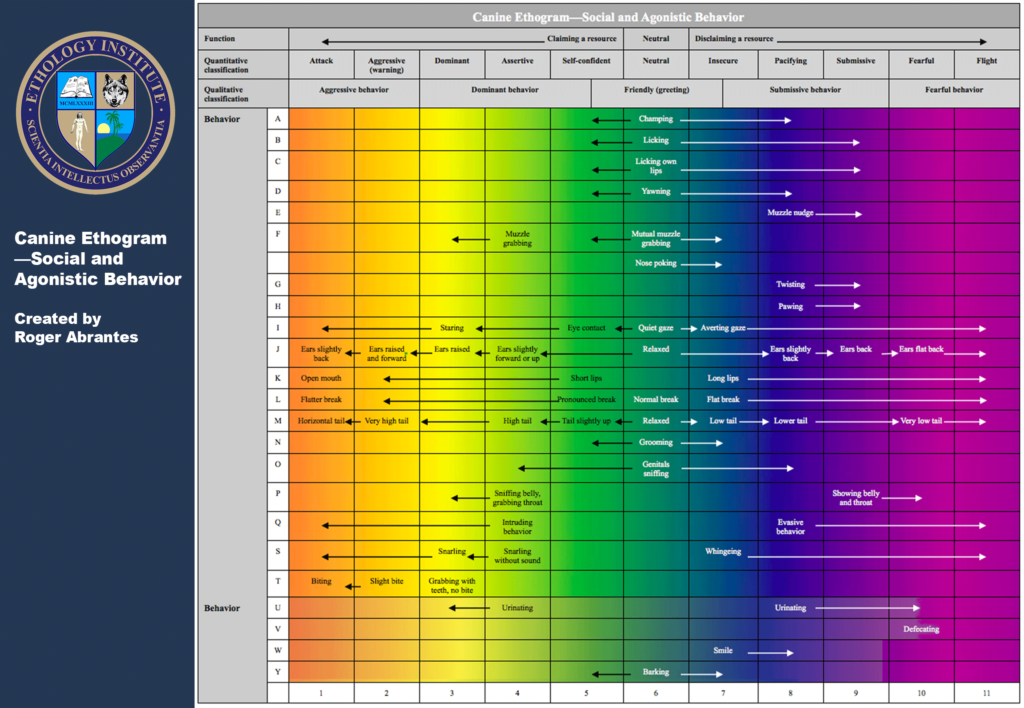

Ethology and Behaviorism Ethology and Behaviorism explains and teaches you how to create reliable relationships with any animal. It is an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach created by ethologist Roger Abrantes.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course All About Puppies, a state-of-the-art online course with everything you need to know about puppies. Choice of puppy, imprinting and socialization, creating good habits and preventing misbehavior, training and stimulating the puppy, house rules and much more. The course everyone should have before acquiring a dog, one all dog trainers should recommend their clients to take when they show up to a class with a puppy. All About Puppies is more than that: it’s the complete dog course.