Bonding in animal behavior is a biological process in which individuals of the same or different species develop a connection. The function of bonding is to promote cooperation.

Parents and offspring develop strong bonds—the former takes care of the latter, and the latter trusts the teachings of the former. As a result of filial bonding, offspring and parents or foster parents develop an attachment. This attachment ceases to be necessary once the juvenile reaches adulthood, but may have long-term effects on subsequent social behavior. Among domestic dogs, for example, there is a sensitive period from the third to the tenth week of age, during which common contacts develop. If a puppy grows up in isolation beyond about fourteen weeks of age, it will not develop the relationships considered normal for species and population.

Males and females of social species develop strong bonds during courtship motivating them to care for their progeny, so they increase the probability of the survival of 50% of their genes.

Social animals develop bonds by living together and having to fend for survival day after day. Grooming, playing, reciprocal feeding, all have a relevant role in bonding. Intense experiences do too. Between adults, surviving moments of danger together is strongly bonding.

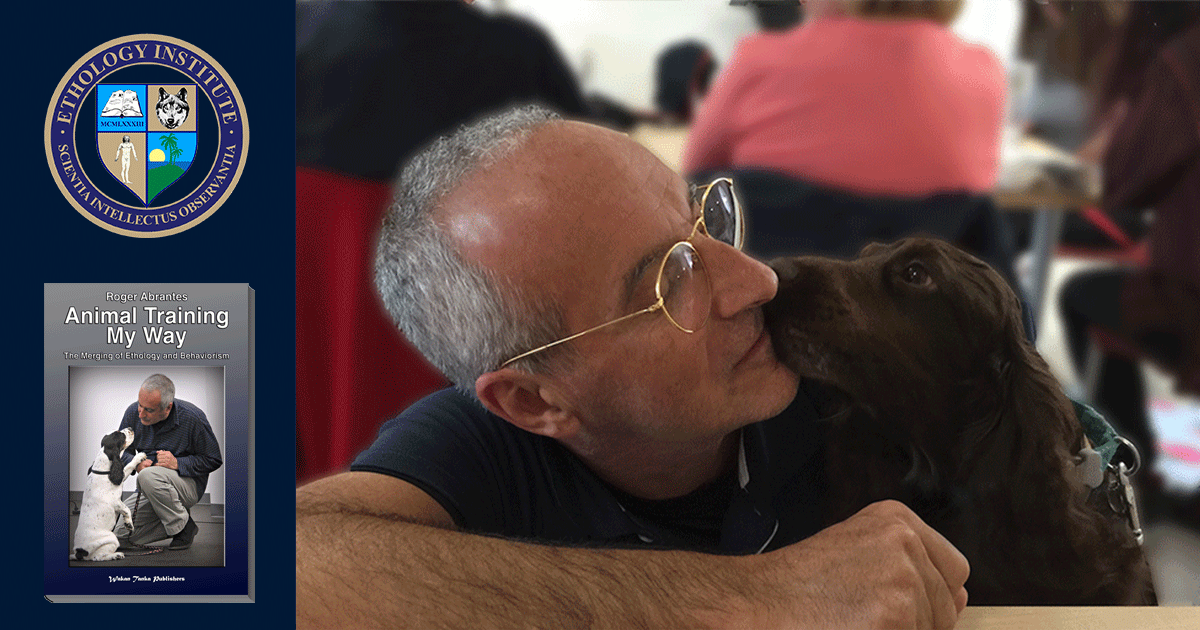

The strongest bonds originate under times of intense experiences (photo by Cuttestpaw).

Behavior like grooming and feeding seems to release neurotransmitters (e.g., oxytocin), lowering the innate defensiveness and increasing the odds of bonding.

We often mention bonding together with imprinting. Even though imprinting is bonding, not all bonding is imprinting. Imprinting describes any phase-sensitive learning (learning occurring at a particular age or a particular life stage) that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences of behavior. Some animals appear to be preprogrammed to learn about certain aspects of the environment during particular sensitive phases of their development. This learning is preprogrammed, in the sense that it will occur without any visible reinforcement or punishment.

Our dogs, in the domestic environment we offer them, develop bonds in various ways. Grooming, resting together, collective barking, and playing and chasing intruders are efficient at creating bonds. Their bonding behavior is by no means restricted to individuals of their species. They bond with the family cat as well and with us, humans.

Bonding is a natural process that will inevitably happen when individuals share responsibilities. Looking into one another’s eyes is only bonding for a while, but surviving together may be bonding for life—and this applies to all social animals, dogs and humans included.

We develop stronger bonds with our dogs by solving problems together rather than by just sitting and petting them. These days, we are so afraid of anything remotely connected to stress that we forget that the strongest bonds originate under times of intense experiences. A little stress doesn’t harm anyone, quite the contrary. I see it every time I train canine scent detection. The easier it is, the quickest it will be forgotten. A tough nut to crack, on the other hand, is an everlasting memory binding the parties to one another.

One of the most exciting scientific discoveries of the latest is on epigenetics. Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene activity not caused in the DNA.

Stress hormones seem to boost an epigenetic process either increasing or decreasing the expression of particular genes. Stress hormones change specific cells of the brain that help memories to be easier retained.

We need to be careful. The term stress is dangerously ambiguous. “Stress is a word that is as useful as a Visa card and as satisfying as a Coke. It’s non-committal and also non-committable,” as Richard Shweder says.* I’m talking about stress in a biological sense, the response of the sympathetic nervous system to some events, its attempts at re-establishing the lost homeostasis provoked by some intense event.

Being an evolutionary biologist, when contemplating a mechanism, I always ask: “What is the function of that? What is it good for?” A behavior can originate by chance (most do), but if it does not confer the individual some extra benefits as to survival and reproduction, it will (most likely) not spread into the population.

Asking the right question is the first step to getting the right answer. Never fear to ask and reformulating your questions. At one point, you’ll have asked the question that will lead you to the right answer.

Why do unpleasant memories seem to stay with us longer than pleasant ones,sometimes even for the rest of our lives?

Situations of exceeding anxiety and stressful, intense experiences create unpleasant memories. It is important, if not crucial, to remember situations that might have hurt us seriously. It makes sense that the stress hormones should facilitate our retaining the memory of events occurring under stress.

Stress hormones do bind to the particular receptors in the brain that enhance the control of the epigenetic mechanisms involved in remembering and, hence, in learning. They do boost the epigenetic mechanisms that regulate the expression of the genes crucial for memory and learning.

Not all stress boosts learning. Too much stress produces the opposite effect. There is a difference between being stressed and stressed out. When we experience far too much stress, our organism goes into an alarm mode where survival has the first and sole priority, and memory formation decreases. Chronic stress does not promote learning either.

Bottom line: we need to be nuanced about stress. Events causing healthy stress responses are necessary for enhancing attention to details, the formation of memory, the creation of bonds, and learning—and too much stress works against it.

___________