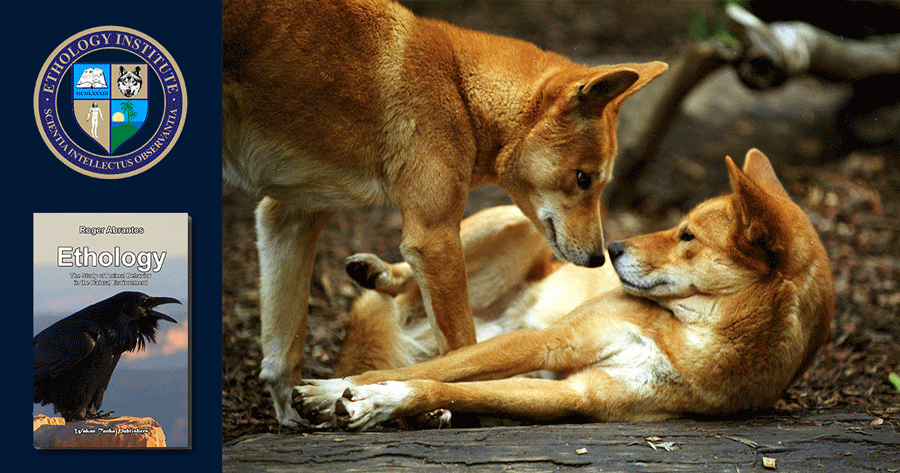

Aggressive and dominant (self-confident) behavior (picture from dogsquad).

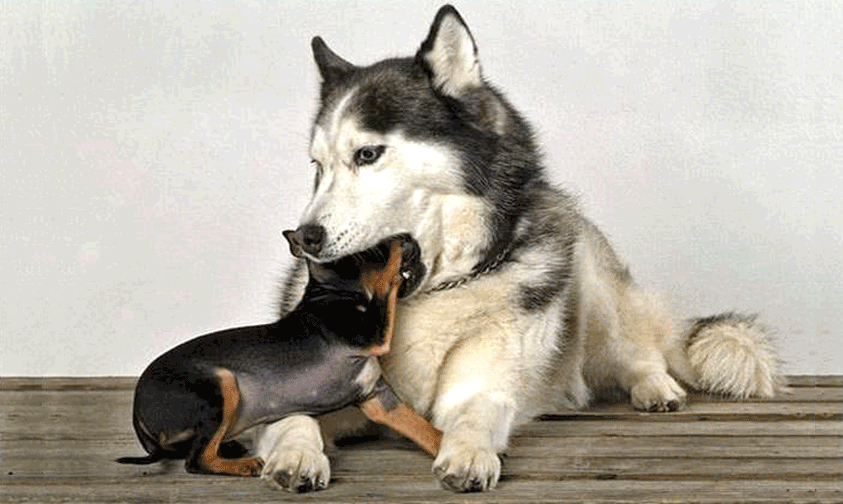

Aggressive and submissive behavior (not fearful).

This is the behavior a cornered dog shows when pacifying, submission and flight don’t work (picture from doggies).

Aggressive and submissive behavior (ears down, long mouth, smaller eyes) (picture Cesar’sWay).

Growling and snarling are also aggressive behaviors (picture askmen)

Contrary to what you might suppose, aggressive behavior is difficult to define. “Lack of agreement regarding definitions of aggressive behavior has been a significant impediment to the progress of research in this area,” writes Nelson in 2005 in his big book ‘Biology of Aggression.’

Why is a good definition necessary? Because only then do we know what we are discussing.

I have never been quite satisfied with my own definition, and it nags me, worse than a mosquito bite, when I can’t come up with a good definition. I have often returned to it changing a comma or two to see if it improved. Alas, to no avail, updated versions were marginally better, but not resoundingly so.

My original definition, let me remind you, was: “Aggressiveness (or aggressive behavior) is behavior directed toward the elimination of competition. It can range from displays of intent, like growling, roaring and stamping to injuring behavior like biting, staging, kicking.”

Not bad, but could be better. I checked many other definitions to analyze their strengths and shortcomings, hoping to get the necessary inspiration to come up with a really good definition.

A— “Aggressive behavior is behavior that causes physical or emotional harm to others, or threatens to. It can range from verbal abuse to the destruction of a victim’s personal property” (www.healthline.com/health/).

Not bad, but not precise enough to use in the biological sciences.

B— “Aggression is a forceful behavior, action, or attitude that is expressed physically, verbally, or symbolically. It may arise from innate drives or occur as a defense mechanism, often resulting from a threatened ego. It is manifested by either constructive or destructive acts directed toward oneself or against others (Mosby’s Medical Dictionary, 8th edition).”

Not bad either, though weakened by the passive voice. It recurs to terms needing strong definitions as well, i.e. drive, defense mechanism. Finally, it is a bit too psychological for the evolutionary biologist—what is a threatened ego?

C— “Aggression is behavior that is angry and destructive and intended to be injurious, physically or emotionally, and aimed at domination of one animal by another. It may be manifested by overt attacking and destructive behavior or by covert attitudes of hostility and obstructionism. The most common behavioral problem seen in dogs.” (http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Aggressive+Behaviour).

This one is not good. It is more a list of synonyms (angry, destructive, hostility, obstructionism) than a definition. It mixes concepts together too easily (aggression and domination?). Finally, the most common problem in dogs in our files (over 10,000 of them) is home alone problems, not aggressive (whatever that is) behavior.

D— “Aggressive people often uses anger, aggressive body language […] “(http://changingminds.org/techniques/assertiveness/aggressive_behavior.htm).

This one, we won’t waste any more time with. A definition that uses the definiendum is not a definition.

E— “Aggression is a response to something/someone the animal perceives as a threat. Aggression is used to protect the animal through the use of aggressive displays (growling, barking, tooth displays, etc.) or protect the animal through aggressive acts (biting). Aggressive behavior is most frequently caused by fear.” (somewhere on the Internet).

This one is not good either. Again, it uses the definiendum in the definition. We miss the definition of threat to be able to analyze the sentence conclusively. More seriously, it states that aggression is caused by fear, which from an evolutionary point of view doesn’t make sense. Fear does not elicit aggressive behavior. It would have been a lethal strategy that natural selection would have eradicated swiftly and once and for all. A cornered animal does not show aggressive behavior because it is fearful. It does so because its natural responses to a fear-eliciting stimulus (pacifying, submission, flight) don’t work.

F— “Aggression is defined as behavior which produced or was intended to produce physical injury or pain in another person.” (Nelson, R. .J. 2005. Biology of Aggression. Oxford Univ. Press).

This is a much better definition, but it could be more explanatory.

So, after yet another round of deliberation, here follows my suggestion.

“Aggressive behavior is behavior directed toward the elimination of competition from an opponent, by injuring it, inflicting it pain, or giving it a reliable warning of such impending consequences if it takes no evasive action. It is distinguishable from dominant behavior in as much as the latter does not include harmful behaviors though it may require some degree of forceful measures. Aggressive behavior ranges from reliable warnings of impending damaging behavior such as growling, roaring, and stamping, to injurious behaviors such as biting, staging, and kicking. Predatory behavior is not aggressive behavior.”

This is much better than earlier versions, and it complies with all the requirements for a good definition. Thus:

- It defines something concrete and observable.

- It states a necessary condition to distinguish it from a related technical term, dominant behavior, even explaining a characteristic of the latter.

- It does not include other terms needing a definition.

- It includes enough conditions to justify the use of the term, not too few to risk being synonymous with another term, and not too many to risk losing its explanatory value by being too encompassing.

- It gives examples of what is and is not aggressive behavior.

- It does not presuppose any special knowledge of the reader to understand it.

This is a good definition because it defines the term, including and excluding the necessary conditions. Whether it will be the last word on the matter is another story. I’m sure it won’t. There is always room for improvement. A good definition must also be able to accept reviews imposed by newer discoveries. Until then, I’m happier with this one than with any earlier versions. Aren’t you?

Learn more in our course Agonistic Behavior. Agonistic Behavior is all forms of aggression, threat, fear, pacifying behavior, fight or flight, arising from confrontations between individuals of the same species. This course gives you the scientific definitions and facts.

Agonistic Behavior is a brand-new, for 2019 created course by leading ethologist Roger Abrantes. It is one of our most challenging courses, addressed to the dedicated student of behavioral sciences.