Do animals have cultural differences? Do dogs behave differently according to their doggy culture?

Yes, they do. Normal behavior is only normal under specific conditions. Normal behavior is the behavior displayed by the majority of the population in a precise area in a particular period. We may not like it, but if most do it, then it is normal. An extreme example: to behave rationally is not normal among humans since most people behave irrationally.

Yes, dogs show cultural differences. Their facial expressions and body languages show slightly different nuances from region to region. Even barking and howling can be distinctive. Davis Mech discovered that when he flew to the Abruzzi Mountains in Italy to assist Luigi Boitani and Erik Zimen with their wolf research. The Italian wolves howled with an accent (or so did the Americans).

Natural selection determines the cultural differences our dogs show from one area to the other. We breed those we like best, and we like them differently from place to place. Remember, selection acts upon the phenotype (the way a dog looks and behaves), but the traits pass to the next generation thru the genes (genotypes) involved in the favored phenotypes. Don’t forget as well that our human choices as to preferred animals are also natural selection.

Cultural differences in dogs are easy to spot when one travels as much around the world as I do. It still surprises me, for example, to see that European English Cocker Spaniels or Bichon Havaneses are so very different from their American counterparts—and not only physically, also behaviorally—same breeds, different cultures.

A culture develops according to the influence of the particular individuals in a group and their distinct environment. The unique characteristics of the individuals and the environment determine cultural development. In dogs, we are the most influential environmental factor. Therefore, the same original breeds develop variants depending on the human group with which they interact. Undoubtedly, we create the various canine cultures we have. The question is whether we do it intentionally or unintentionally, and I believe we can argue for both.

In a sense, we can say we have the dogs we deserve. We have created them, either by planning to breed them to achieve specific results or not caring at all—which amounts to the same in this context. The problem is that cultures evolve, our societies change, and so do our needs and requirements—which is fair enough. What does not seem fair to me is to impose new (cultural) requirements upon the dog all of a sudden after having created it to fulfill different (cultural) needs back in the day. Of course, we (as a species) change with time, and so do our dogs. We can change them, the dogs, to meet new necessities, as we’ve done in the past, but it requires a well-planned breeding program based on reasonable expectations and scientifically sound methods.

The ethics of changing animals as we please is an entirely different discussion, alas one for another day.

References

Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi L (1986). “Cultural Evolution”. American Zoologist. 26 (3): 845–855. doi:10.1093/icb/26.3.845.

Davis, N.B.; J.R. Krebs, J.R.; West, S.A. (2012). An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology (4th ed.). ISBN-10:9781405114165.

De Waal, Frans. (2001). The Ape and the Sushi Master: Cultural Reflections by a Primatologist. New York: Basic Books.

Holdcroft, D.; Lewis, H. (2000). “Memes, Minds, and Evolution.” Philosophy. 75 (292): 161–182.

Jones, Nick A. R.; Rendell, Luke (2018). “Cultural Transmission.” Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Springer, Cham. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1885-1. ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6.

Laland, Kevin N. and Bennett G. Galef, eds. (2009). The Question of Animal Culture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard UP.

Swanson, H.A., Lienand, M.E., Ween, G.B. (2018). Domestication Gone Wild: Politics and Practices of Multispecies Relations. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822371649.

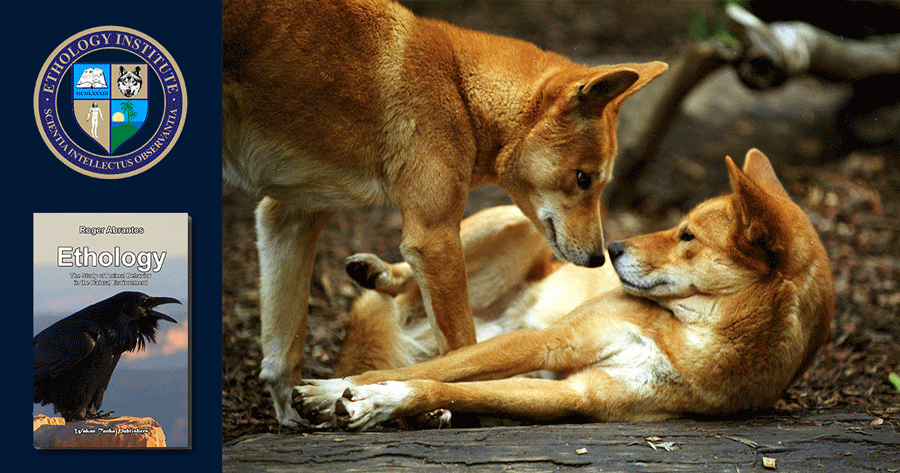

Featured image: Dog behavior shows cultural differences across breeds and regions (photo by NewEvolution at https://newevolutiondesigns.com/50-free-hd-dog-wallpapers).

Featured Course of the Week

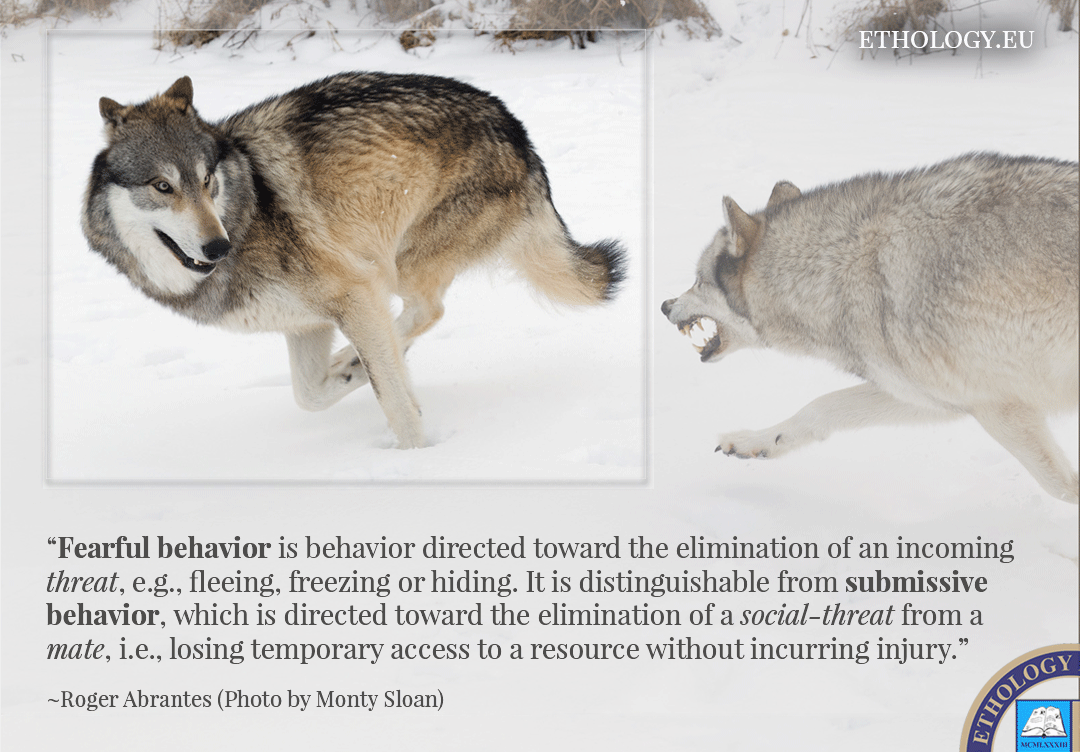

Ethology and Behaviorism Ethology and Behaviorism explains and teaches you how to create reliable relationships with any animal. It is an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach created by ethologist Roger Abrantes.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.