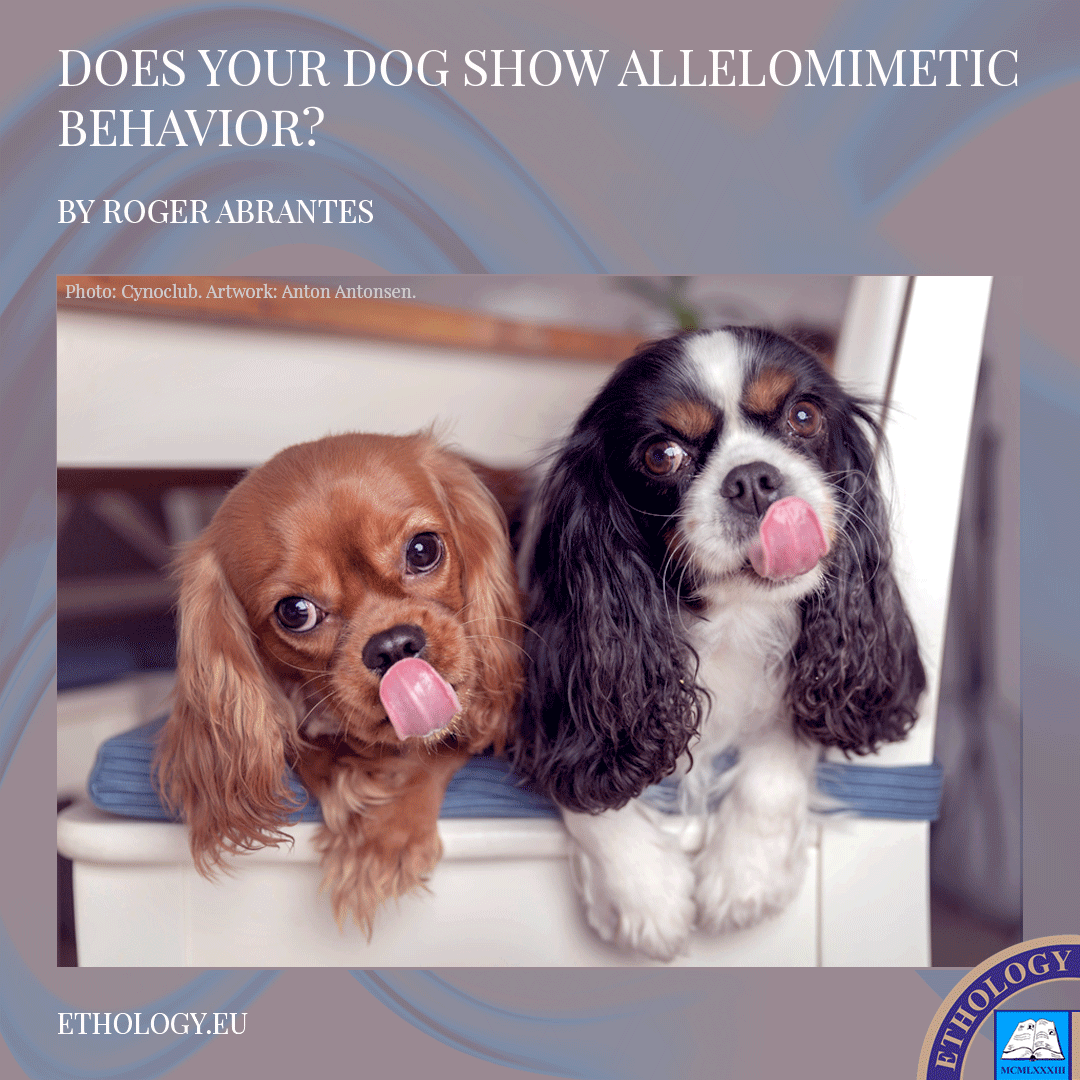

Does your dog show allelomimetic behavior? I’m sure it does but don’t worry, it’s not dangerous, except when it is, and yes, it is contagious. Confused? Keep reading.

Allelomimetic behavior is doing the same as others do. Some behaviors have a strong probability of influencing others to show the same behavior. Animals keeping in constant contact with one another will inevitably develop allelomimetic behavior.

Dogs show various instances of allelomimetic behavior—walking, running, sitting, lying down, getting up, sleeping, barking, and howling have a strong probability of stimulating others to do the same.

Social predators increase their rate of hunting success when they function in unison. One individual setting after the prey is likely to trigger the same response in the whole group.

More often than we think, it is our own behavior that triggers our dog’s allelomimetic behavior (photo by SunVilla).

The wolf’s howl is allelomimetic, one more behavior our domestic dogs share with their wild cousins. Howling together functions as social bonding. When one wolf howls, the whole pack may join in, especially if a high-ranking wolf started it. I bet that if you go down on your knees, turn your head up, and howl, (provided you are a half-decent howler) your dog will join you; then, it will attempt to show its team spirit by licking your face.

Sleeping and eating are examples of allelomimetic behavior. Dogs and cats tend to sleep and eat at the same time. Barking is also contagious. One barking dog can set the whole neighborhood’s dogs barking.

Synchronizing behavior may be a lifesaver. In prey animals like the deer, zebra or wildebeest, one individual can trigger the whole herd to flee. This trait is so important for self-preservation that farm animals like sheep, cows, and horses still keep it. Grazing also occurs at the same time.

Running after a running child is more often an example of canine allelomimetic behavior than hunting or herding as many dog owners erroneously presume.

Allelomimetic behavior is not restricted to animals of the same species. Animals of different species who live together show allelomimetic behavior regularly. Dogs are able body language readers and respond to certain behaviors of their owners with no need for further instruction. An alerted owner triggers his dog’s alertness more often than the opposite.

Puppies show allelomimetic behavior at about five weeks of age. It is an intrinsic part of your dog’s behavior to adjust to the behavior of its companions. Your behavior influences your dog behavior in many more instances than you realize.

Since we have selected and bred our dogs to be highly sociable and socially promiscuous, they show extended allelomimetic behavior, not only copying the behavior of their closest companions but of others. Next time you walk in the park and your dog runs after running children, you can casually comment, “Typical instance of allelomimetic behavior.” Not that it will solve any problem, if there is one, but you’ll be right and I bet you will impress more than a few of your fellow park walkers.

Featured photo by Cynoclub. Artwork by Anton Antonsen.

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology and Behaviorism Ethology and Behaviorism explains and teaches you how to create reliable relationships with any animal. It is an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach created by ethologist Roger Abrantes.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.