Wouldn’t it be nice if we all gave expecting nothing in return? What a beautiful world we would have. At one time or another, most of us have embraced such thoughts. But is it possible at all? Is it possible for all of us to become givers—no takers at all?

An evolutionary biologist will tell you, right away, it is not possible. Every behavioral strategy, when adopted by everyone in a group, is vulnerable to any variation or mutation that will carry a slight advantage. Were we all to become givers, we would be at the mercy of the first taker that would show up. More takers would follow for if it works for one, it also works for others.

All relationships are a trade, a “give and take.” How much we give and how much we take depends on the benefits and costs involved. The goal is to come out of any trade with a profit. Occasional deficits are acceptable as long as the overall balance stays on the plus side. That is the law of life. We spend energy to gain energy, to keep alive. Sometimes, we need to plan long-termed. There are both benefits and costs that we do not incur immediately. The law is still the same: the balance must end up on the positive side, or life will end.

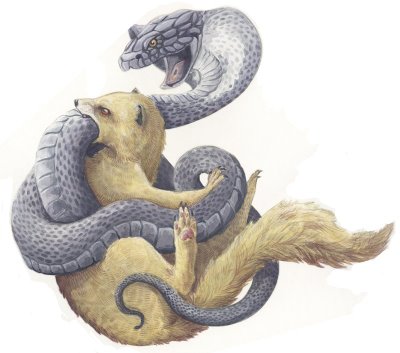

Apart from our dream of a better world full of unselfish givers, it looks at first sight as taking and not giving is the most profitable strategy. The problem is that we cannot all be takers. Takers can’t take from takers; they can only take from givers. Thus, it would appear that the givers would always be at a loss, but that is not the case. Givers receive from other givers, and they don’t spend energy fighting with takers. On the other side, takers spend energy when facing other takers, gaining nothing. While giver/giver allows both to come out on the plus side of the balance, taker/taker always comes out with a deficit.

Givers and takers keep each other at bay. The ideal number for each, so that there is stability, depends solely on the value of benefits and costs.

To analyze how different strategies influence one another, the evolutionary biologist strips the strategies to their core and assigns some values to the variables, i.e., benefits and costs.

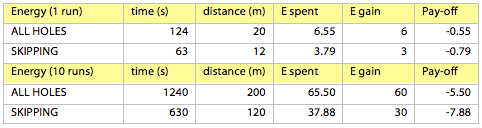

Let’s assume that when a taker meets a taker, they benefit nothing and spend much energy. When a giver meets another giver, they both give and take equally, and they spend some energy (they have both benefits and costs). When a taker meets a giver, the taker benefits 100%, and the giver spends energy (costs). We set the value of benefits and costs as follows:

- benefit (b) 20 (conferred by the givers to anyone)

- cost (c) -5 (the cost of giving)

- taker/taker cost (e) -50 (this is the energy takers spend when fighting one another to take without giving).

Let’s now calculate the percentage of takers and givers necessary to achieve an equilibrium so that both strategies give the same profit.

The proportion of takers = t

The proportion of givers (g) = (1-t)

The average payoff for a giver (g) is G = ct + (b+c)(1-t)

The average payoff for a taker (t) is T = et + b(1-t)

There is an equilibrium (stability) when G=T.

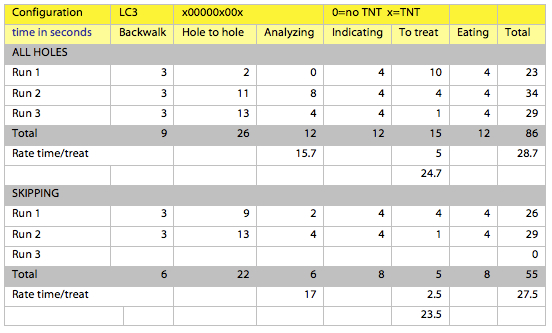

| Strategy | Opponent’s strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Takers | Givers | |

| Takers | e | b |

| Givers | c | b+c |

Example 1—With the above values for benefits and costs, a combination of 10% takers and 90% givers gives both a profit of 13, and there is stability. If the cost of takers fighting one another decreases, then it pays off (for more individuals) to become a taker.

Example 2—The figures in example 1 seem to suggest that takers should avoid one another as much as possible. Let’s say they do it in three out of four times. Then, and still with the same values, the number of takers can rise to 40%, and we still have an equilibrium, i.e. an ESS (Evolutionarily Stable Strategy). However, the profit will be less for both givers and takers, namely 7—more takers equals less profit for all.

That is a good example of what happens in a capitalistic human society dominated by greed, taking more and more. Takers take all they can but end up poorer than if they took less. The capitalistic instinct says, “take more,” but a more rational approach shows that taking less amounts to more profit. The strategy of taking maximally works only for a limited time. After a time, it backfires (depression, recession, etc.) because it upsets the balance between the feasible strategies, which, by then, have become evolutionarily unstable.

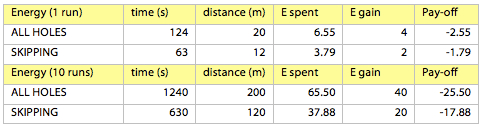

Example 3—Encounters between takers are very expensive. What if takers would avoid takers all the time? In this case, the number of takers can rise to 80%. Beyond that, the strategies become evolutionarily unstable. The interesting is that even though there would be stability with such a high number of takers, both takers and givers would come at a loss of -1. That is not at all a healthy strategy for any individual, let alone a group. It’s the sign of a society in decay. It’s what happens in a group dominated by greed and selfishness.

Example 4—Since our wish is a world full of givers let us see how we can maximize the number of givers. We need to change the values for benefits and costs. Let’s decrease the cost of giving and increase the costs incurred by takers when fighting one another.

- benefit (b) 20 (remains the same)

- cost (c) -1 (lower cost than above)

- taker/taker cost (e) -100 (much higher cost than above)

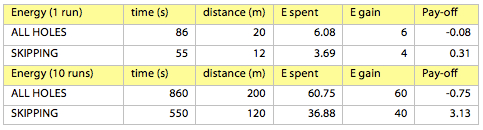

With these values, we can reach a maximum of 99% givers versus 1% takers. Both will have a profit equal to 18.80. Note that this the highest achieved payoff in all our simulations.

The only variables that reduce the number of takers are the cost (e) and the probability of facing another taker. If we keep the values of benefits and costs the same as initially (b=20, c=-5) the costs of the struggle between two takers must rise to -500 for the strategies to be evolutionarily stable. Then, the profit becomes 14.80 instead of 18.80.

These are artificial figures to analyze the needed conditions for an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy to emerge. We may question the unlikeliness of the costs of any interaction to rise as high as we have set the taker/taker encounters. And yet, conflicts between male Northern elephant seals, Mirounga angustirostris, often end with a critical injury or the death of one of the parties. The costs are high, but so are the benefits: in Northern elephant seals, fewer than 5% of the males perform 50% or more of the copulations. A red deer stag, Cervus elaphus, has about a 25% chance to incur a permanent injury from fighting (like in our example 2).

Also interesting is that the value of the benefits does not change the proportion of takers versus givers, only the profit. For example, with b=40, the profit is 34.60 (versus18.80 and 14.80 for the other values for benefits in the examples). The values we used are all fictive, but it doesn’t matter. They show the trends created by increasing or decreasing a variable. To test real situations, we can use realistic figures whenever we can get them. We can assign values to benefits and costs according to gain or loss of calories, body weight, the number of progeny, available mating partners, fitness or even quality of life (if we find a reliable way to measure it).

The conclusion is that there will always be givers and takers—or that any strategy needs a counterpart to form an ESS. We can influence the trend of adopting one or the other strategy with the benefits and costs involved, but we can’t eliminate either one completely—and this is the universal law of life. In other words, every mountain has a sunny and a shady side.

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology and Behaviorism Ethology and Behaviorism explains and teaches you how to create reliable relationships with any animal. It is an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach created by ethologist Roger Abrantes.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.