For the umpteenth time, a reinforcer is not a reward. When I hear “Force-Free” trainers say, “dogs like to work to earn rewards,”1 I suspect and fear they miss by a mile and a half the essence and function of reinforcers in learning theory (and so also of inhibitors).

I’m not splitting hairs. There is a crucial difference between “reinforcing a particular behavior” and “rewarding an individual.” I suspect ignorance hereof being as well the cause of the many incorrect statements on inhibitors2 from the “Radical Force-Free” camp (emphasis on radical).3

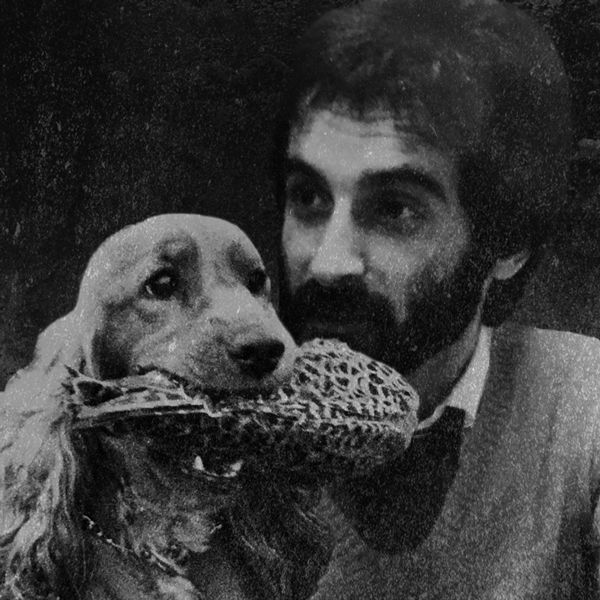

“Dogs like to work to earn rewards” reminds me somehow of the old days when I opposed the old school of military dog training. Not everything was hassle and squabble; we had our moments of pleasantries. After ten minutes of marching forth and back, the instructor would say, “And halt! Now, praise your dogs.” Yes, I went to that kind of dog training with my first dog. That was what we had by then.

I walked out in disgust and decided, there and then, my dog and I would train by ourselves and we would show them. We did.

I substituted praise with reinforcers, the real thing—not rewards,—including my ‘dygtig’4 and treats given at strategic points. I stopped using a leash and started using a lead. Leash jerks gave place to “No” immediately followed by “dygtig” when the dog, not me, corrected the mistake. That, my dog would undisputedly do because she visibly enjoyed being my “teammate.” I was a student of ethology and I knew about social canines, our domestic dog being one. Old Professor Lorenz’s words rang in my ears, “To understand an animal, first you have to become a partner,” and he knew better than anyone for he had done it with his goslings.

I signed up for the final “obedience” competition at the club, a hunting dog club run by real hunters, and we won with max points. That a young long-haired fellow in faded Levi’s and clogs had won created some agitation; and, as to add insult to injury, my dog was a little, only seven-months-old English Cocker Spaniel (a genuine one, not one of those oddballs we see in the US today), red and female, on top of that. Petrine was intelligent, beautiful, charming, a workaholic, and a sweety-pie—though I might be a tad biased.

Our performance generated some raised eyebrows and more humming than the establishment would have wished. At the prizes and punch social function, a few civilians asked me whispering whether I would help training their fidos (read companion dogs).

The following Saturday, we were training on a grass field across the road where I lived, now the local firemen’s station. That was 1982, the summer before my son Daniel was born; and that’s how dog training came into my life. I never planned it.

Two years later, in 1984, I wrote my first book, “Psychology Rather than Force,” with far too little experience but loads of good ideas including force-free, hands-free, reinforcement-based training with as few inhibitors as possible, and it even included a whistle (the precursor of the clicker).

I was positive dog training would change. It did, and the rest is history.

__________

Notes

1 – This is an actual quote from a document published on the internet by a confessed “Force-Free” trainer.

Note that Skinner writes about reinforcers and rewards, “The strengthening effect is missed, by the way, when reinforcers are called rewards. People are rewarded, but behavior is reinforced. If, as you walk along the street, you look down and find some money, and if money is reinforcing, you will tend to look down again for some time, but we should not say that you were rewarded for looking down. As the history of the word shows, reward implies compensation, something that offsets a sacrifice or loss, if only the expenditure of effort. We give heroes medals, students degrees, and famous people prizes, but those rewards are not directly contingent on what they have done, and it is generally felt that the rewards would not be deserved if they had been worked for.” (Skinner, 1986, p. 569).

2- In 2013, I suggested we changed punisher and derivatives to inhibitor and derivatives to avoid the moral and religious connotations of the former, particularly in the Latin languages, and to emphasize its function and use as a learning tool.

3 – “Radical Force-Free dog trainers” (also “radical positives”) is my denomination for those trainers adhering to the positive reinforcement-based or force-free movement, but having extreme views like claiming positive reinforcers are the only learning tool one needs, they never use aversive stimuli, one should never say “no,” everyone else but them is wrong, and other absurdities. Please do not confuse them with the non-radical positive or reinforcement-based dog trainers who are equally force-free but sensible, open-minded, prudent in their claims, and polite and considerate to otherwise thinkers.

4 – “Dygtig” is my preferred semi-conditioned sound reinforcer. It’s a Danish word meaning’ clever,’ ‘skilled.’ It has a good doggy sound.

References

Abrantes, R. 1984. Psykologi Fremfor Magt (Psychology Rather Than Force). Lupus Forlag.

Abrantes. R. 2013. The 20 Principles All Animal Trainers Must Know. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

Skinner, B. F. 1986. What is wrong with daily life in the Western world? American Psychologist, 41(5), 568-574. Retrieved Jun. 29, 2019.

Featured photo by Annemarie Abrantes.

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology and Behaviorism Ethology and Behaviorism explains and teaches you how to create reliable relationships with any animal. It is an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach created by ethologist Roger Abrantes.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology and Behaviorism. Based on Roger Abrantes’ book “Animal Training My Way—The Merging of Ethology and Behaviorism,” this online course explains and teaches you how to create a stable and balanced relationship with any animal. It analyses the way we interact with our animals, combines the best of ethology and behaviorism and comes up with an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach to animal training. A state-of-the-art online course in four lessons including videos, a beautiful flip-pages book, and quizzes.