JG is a rat, a Cricetomys gambianus or Giant Gambian Pouched Rat; she is also a Hero Rat, a landmine detector at Apopo in Tanzania. In December 2009, she performed uncharacteristically badly and puzzled everybody as Hero Rats don’t make mistakes. What was the problem with JG? Had she lost it? Had the trainers made a crucial mistake?

Apopo in Morogoro, Tanzania, trains rats to detect landmines and tuberculosis and the little fellows are very good at what they do. In Mozambique, Apopo has so far cleared 2,063,701 square meters of Confirmed Hazardous Areas, with the destruction of 1866 landmines, 783 explosive remnants of war and 12,817 small arms and ammunition. As for tuberculosis, up until now, the rats have analyzed 97,859 samples, second-time screened 44,934 patients, correctly diagnosed 7,662 samples and discovered 2,299 additional cases that were previously missed by the DOTS centers (Direct Observation of Treatment, Short Course Centers in Tanzania). More than 2,500 patients have since been treated for tuberculosis after having been correctly diagnosed by the rats.

In December 2009, I was working full time at Apopo in Morogoro. I wrote their training manual, trained their rat trainers, supervised the training of the animals and analyzed standard operating procedures. At the time of writing, I still do consultancy work for Apopo and instruct new trainers from time to time. Back then, one of my jobs was to analyze and monitor the rats’ daily performance and that’s when I came across the peculiar and puzzling behavior of JG in the LC3 cage.

Problem

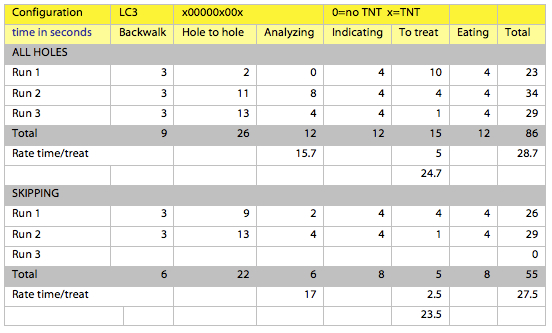

LC3 is a cage with 10 sniffing holes in a line and the rats run it 10 times. On average, 21 holes, randomly selected by computer, will contain TNT samples. We train rats in LC3 every day, recording and statistically analyzing each session. We normally expect the rats to find and indicate the TNT samples with a success rate of 80-85%. Whenever the figures deviate from the expected results, we analyze them and try to pinpoint the problem.

On December 19, we came across a rat in LC3 that did not indicate any positive samples placed from Holes 1 to 6. She only indicated from Holes 7 to 10. In fact, from Hole 1 to 6, Jane Goodall (that’s the rat’s full name) only once bothered to make an indication (which was false, by the way). From Hole 7 to 10, JG indicated 10 times with 9 correct positives, only missing one, but also indicated 11 false positives. Her score was the lowest in LC3 that day and the lowest for any rat for a long time. What was the problem with JG? She seemed fine in all other aspects and seemed to know what she was doing. Why then did she perform so poorly?

Giant Gambian Pouched Rat searching TNT in a line cage (photo by Silvain Piraux).

Analysis of searching strategies

Whenever an animal shows such a behavior pattern, and it appears purposeful rather than emotional, I become suspicious and suspect that there is a rational explanation.

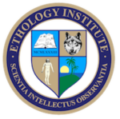

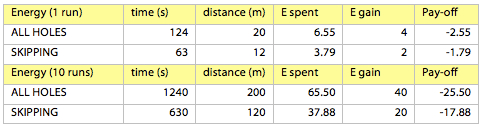

In order to analyze the problem, I constructed simulations of two searching strategies: (1) searching ALL HOLES, and (2) SKIPPING Holes 1 to 5 (I didn’t want to be as radical in my simulation as JG). In addition, I ran simulations with two different sample placement configurations: (1) evenly distributed between the two halves, i.e. two positives in Holes 1 to 5 and two positives in Holes 6 to 10; and (2) unevenly distributed — one positive in the first five holes and two positives in Holes 6 to 10.

In order to run the simulation, I needed to assign values to the different components of the rat’s behavior. I chose values based on averages measured with different rats.

- Walking from feeding hole to first hole (back walk) = 3 seconds.

- Walking from covered hole to covered hole = 1 second.

- Walking from uncovered hole to uncovered hole = 2 seconds.

- Analyzing a hole = 2 seconds.

- Indicating a positive = 4 seconds.

- Walking from last hole to feeding hole = 1 second.

- Eating the treat = 4 seconds.

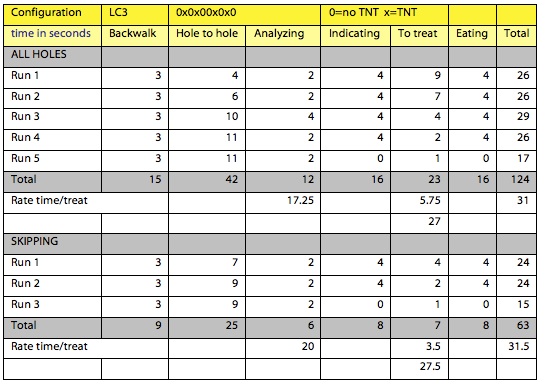

All time variables were converted into energy expenditure in the calculation of energy payoff for the two strategies and the different configurations. Also the distance covered was converted into energy expenditure. The reinforcers (treats) amounted to energy intake. In my simulation I used estimated values for both expenditure and intake. However, we could measure all values accurately and convert all energy figures into kJ.

The results

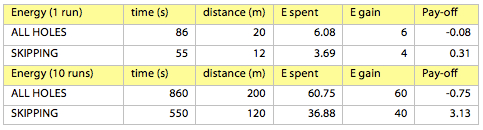

In terms of energy, (in this simulation I make several assumptions based on reasonable values, e.g. the total energy spent is a function of distance covered and time spent), the results show that when the value of each treat is high (E gain is close to the sum of all treats amounting to the sum of energy spent for searching all holes), it pays off to search all holes (the loss of -5.50 versus -7.88). The higher the energetic value of each treat, the higher the payoff of the ALL HOLES strategy.This is a configuration with four positives (x) and six negatives (0). The results show that neither strategy is significantly better than the other. On average, when sniffing all holes, the rat receives a treat every 31 seconds, while skipping the first five holes will produce a treat every 31.5 seconds. However, there is a notable difference in how quickly the rat gets to the treat depending on which strategy the rat adopts. ALL HOLES produces a treat on average 5.75 seconds after a positive indication. SKIPPING produces a treat 3.5 seconds after a positive indication. This could lead the rat to adopt the SKIPPING strategy, but it’s not an unequivocally convincing argument.

However, when the energetic value of each treat is low, skipping holes will reduce the total loss (damage control), making it a better strategy (-17.88 versus -25.50).

However, if we run a simulation based on an average of three positives per run, with one in the first half and two in the second half (which is closest to what the rat JG was faced with on December 12), we obtain completely different results. This first analysis does not prove conclusively that the SKIPPING strategy is the best. On the contrary, it shows that, all things considered, ALL HOLES will confer more advantages.

The energy advantage is also detectable in this configuration, even when each treat has a high energetic value (a gain of 3.13 versus a loss of -0.75).With this configuration, the strategy of SKIPPING is undoubtedly the best. On average, it produces a reinforcer every 27.5 seconds (versus 28.7 for ALL HOLES) and 2.5 seconds after an indication (versus 5 seconds).

Conclusion

This second simulation proves that JG’s strategy was indeed the most profitable in principle. However, the actual results for JG are completely different from the ones shown above, as they also have to take into account the amount of energy spent indicating false positives (which are expensive).

It is now possible to conclude that the most advantageous strategy is as follows. Whenever the possibilities of producing a reinforcer are evenly distributed, search all holes. It takes more time, but on average you’ll get a reinforcer a bit quicker than if you skip holes. In addition, you either gain energy by searching all holes, or you limit your losses, depending on the energetic value of each reinforcer. Don’t be fooled by the fact you get a treat sooner after your indication when searching all holes then when skipping.

Whenever the possibilities of producing a reinforcer are not evenly distributed, with a bias towards the second half of the line, skip the first half. It doesn’t pay off to even bother searching the first half. By skipping it, you’ll get a lower total number of reinforcers, but you’ll get them quicker than searching all holes and, more importantly, you’ll end up gaining energy instead of losing it.

Finally, avoid making mistakes by indicating false positives. They cost as much as true positives in spent energy, but you don’t gain anything.

An evolutionary explanation

Of course, no rat calculates energetic values and odds for certain behaviors that are reinforced, nor do they run simulations prior to entering a line cage. Rats do not do this in their natural environment either. They search for food using specific patterns of behavior, which have proven to be the most adequate throughout the history and evolution of the species. A certain behavior in certain conditions, depending on temperature, light, humidity, population density, as well as internal conditions such as blood sugar level etc., will produce a slightly better payoff than any other behavior. Behaviors with slightly better payoffs will tend to confer slight advantages in terms of survival and reproduction and they will accumulate and spread within a population; they will spread slowly, for the time factor is unimportant in the evolution of a trait. Eventually, we will come across a population of individuals with what seems an unrivalled ability to make the right decision in circumstances with an amazing number of variables, and it puzzles us because we forget the tremendous role of evolution by natural selection. Those individuals who took the ‘most wrong decisions’ or ‘slightly wrong’ decisions inevitably decreased their chances of survival and reproduction. Those who took ‘mostly right’ or ‘slightly righter’ decisions gained an advantage in the struggle for survival and reproduction and, by reproducing more often or more successfully, they passed their ‘mostly right’ or ‘slightly righter’ decisions genes to their offspring.

This is a process that the theory of behaviorism cannot explain, however useful it is for explaining practical learning in specific situations. In order to explain such seemingly uncharacteristic behaviors, we need to recur to the theory of evolution by natural selection. This behavior is not the result of trial and error with subsequent reinforcers or punishers. It is an innate ability to recognize parameters and behave in face of them. It is an ability that some individuals possess to recognize particular situations and particular elements within those situations, and correlate them with specific behavior. What these elements are, or what this ability exactly amounts to, we do not know; only that it has been perfected throughout centuries and millennia, and innumerable generations that accumulate ‘mostly right’ or ‘slightly righter’ decisions—and that is indeed evolution by means of natural selection.

Featured image: Giant Gambian Pouched finds a landmine (photo by Xavier Rossi).

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology and Behaviorism Ethology and Behaviorism explains and teaches you how to create reliable relationships with any animal. It is an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach created by ethologist Roger Abrantes.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.