The weather is nearly always hot and sunny, between 29º and 38ºC (85º and 100º F), Today it’s exactly 32º C according to my diving computer. Of course it rains during the rainy season, but only for an hour or two and everything soon dries off, leaving a sense of freshness and the smell of wet soil in the air. Sometimes it rains cats and dogs, turning the streets in the village into small rivers, but everyone takes it in their stride and, with shoes off and pants rolled up, life continues (literally) with a smile.

After having completed three dives, one of them in a strong surge, I’m starving as usual. These days, in my ageing youth, my job in Thailand is marine biology environmental management, which, basically, means I dive, sometimes with students, sometimes without, take pictures of the fish and corals I see, and then write a report—yes, I call that a job! I stop at one of those remarkable street vendors on the main street to grab something to eat. ‘Street food’ is so cheap and so good that it doesn’t make any sense to go home and cook.

Buddhist Monk and Dog (image by John Lander).

My favorite ‘restaurant’ (it looks more like an open garage) is a family business, like most small businesses in Thailand. The owners live there too. They have a TV and a bed for the kids in the back—that is, behind the four tables for the guests. It’s all on view for all to see. Of course, you don’t want to isolate the kids in a room by themselves. Children (and dogs) are an inherent part of Thai life; you see them everywhere. They are allowed to do whatever they want, are seldom scolded or yelled at and, amazingly enough, they are pretty well-behaved. It puzzles me how they manage it, especially when I think of some of our little brats in the West, both human, and canine. I am yet to discover their secret, but I guess it has something to do with the fact they are part of every aspect of daily life from the day they are born; they are perfectly integrated with no artificially constructed, designated kids-zones. The same goes for the dogs, they belong there like anyone else: no fuss, no extra attention, no special treatment one way or another.

“Sawasdee kha khoon Logel,” Phee Mali greets me with a big smile when she sees me.

Phee means big sister and Mali means Jasmine, which is her name. I’m Logel because Thais are always on first name terms. Last names are a relatively new invention imposed on them by the government in response to the growth of the nation and a more modern society. The telephone directory is ordered by first names. King Rama VI introduced the practice of surnames in 1920 and he personally invented names for about 500 families. All Thais have nicknames. You call your friends by their nicknames and sometimes you don’t even know their real name! I’m Logel because most Thais can’t pronounce the ‘r’ sound, not even in their own language and, surprisingly enough, they do have ‘r’ in Thai.

Thais often take the dogs to the local temple so they can die in peace, in the company of the monks, near Buddha.

“You OK, you see beautiful fish today?” Phee Mali asks me in ‘Tenglish’—or Thai English, which is a language in its own right, most charming and highly addictive. Before long and without even noticing it, you begin speaking Tenglish. I speak a mixture of Thai and Tenglish with the locals. As my Thai improves, I speak more Thai and less Tenglish, but Thai is difficult as it is a tone language. The tone with which you pronounce a word changes its meaning and sometimes dramatically so. There are words I consistently mispronounce which has the Thais in fits of laughter, either because I talk utter nonsense, or I say something naughty. They love it when it’s the latter. They even encourage me to say something they know I can’t pronounce just to amuse themselves. It’s all good-hearted and good fun, with no disrespect intended. On the contrary, I get preferential treatment because I speak Thai. I’ll transcribe below some of our conversations in English, directly translated from the Thai words, in order to give my readers a feel for it.

“Yes,” I answer, “I saw beautiful fish and corals. Thale (sea) Andaman very good.”

“Oh you so black!” she exclaims with furrowed brows and a smile. ‘Black’ actually means either tanned or sun burnt, as the case may be. Thai women don’t like to be sun tanned. They like white, as they say, and they become very worried when they see someone with what in the West we call a healthy, attractive tan.

“You hung’y ‘ight, gwai teeaw moo pet mak ‘ight?” Phee Mali asks me laughing. She knows just what’s on my mind—I love a hot, spicy gwai teeaw moo, especially after a hard day’s work. It’s a soup, containing noodles and pork, chicken or shrimp, with everything else imaginable thrown in. It even comes with a side plate of fresh vegetables that you tear into pieces with your fingers and add to the soup as you please. You season it all yourself with dry chili, fresh chili, chili sauce, fish sauce, soy, pepper, salt, and a bit of sugar (yes sugar, try it and you’ll see why I love it). It’s delicious I can assure you, and healthy too.

I eat my gwai teeaw moo and sip down my iced green tea, no sugar. The sun will set in about half an hour; it always goes down at the same time here, seven degrees north of the equator. No rain today. I relish life in Paradise!

“Tao thale sa baay dee mai.” The kids come running to ask me about the fish and especially the sea turtle, their favorite—which is a good opportunity for me to practice my Thai language. They call me Lung Logel (Uncle Roger), in deference to my age. Then, it’s the dogs’ turn to say hi—in Doggish, one language I do know, no accent and spoken the same on every continent.

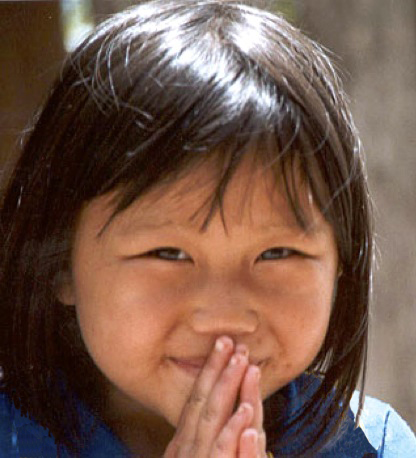

The wai is the Thai greeting when you raise both hands together to your chin. It still strikes me as the most beautiful greeting I’ve ever seen.

I see Ae on the other side of the street (Ae is a funny name deriving from the Thai peekaboo game). I know her and her family. Her father works on one of the boats I regularly sail with on my diving tours. I often help him dock the boat when we arrive at the pier in less than perfect weather and we sometimes have a beer together after having secured the boat, unloaded, etc. Ae is squatting beside her dog, one of those Thai dogs that looks the same as every other. Village dogs in Thailand all look alike, as if they were a particular breed, the product of random breeding throughout the years. I call them ‘default dogs.’

“Ae sad, right?’ I ask the kids.

“Oh, dog Ae old already, tomorrow father of Ae bring dog to go temple,” Chang Lek (Little Elephant is his name) replies.

I finish my meal and go over to talk to Ae, still squatting beside her dog and petting him. I can see Bombom is old and tired. He’s a good, friendly dog. He can often be seen strolling around the village, quietly surveying the neighborhood. He’s always incredibly dusty despite Ae and her mother painstakingly and frequently bathing him. When I approach them, he barely raises his head. He gives me that affable, resigned look of his.

“Sawasdee khrap, Ae.”

“Sawasdee kha,” she says to me and hastens to wai to me. The wai is the Thai greeting when you raise both hands together to your chin. It still strikes me as the most beautiful greeting I’ve ever seen.

“Bombom is old, right?” I ask her.

“Yessir.”

“Bombom already had happy life. You are good friend of Bombom.”

“Yessir,” she says gently.

“Bombom likes you very much,” I say, lost for words.

“Tomorrow Mom and Dad bring Bombom to go to temple,” she replies and I see a big tear roll down her left cheek.

“Yes. I know,” I tell her. Again lost for words, I add “Ae, I go across the street to buy ice cream for us to sit here eating ice cream and talking to Bombom. You like that?”

“Yessir, thank you so much sir,” she says and manages to give me a lovely smile. “Bombom likes ice cream so much,” she adds and her eyes are now full of thick, sorrowful, young tears.

In Thai culture and beliefs, all living beings under the sun deserve the same respect. Species is of no relevance. They love their pets and when they are old and dying, some Thais take them to the local temple so they can die in peace, in the company of the monks, near Buddha. That’s why there are always many dogs around the temples, which sometimes is a real problem. The temples are poor. A monk owns only seven articles. The villagers cook for them (and the dogs) in the morning before going to work.

Sawasdee khrap,

ชีวิตที่ดี

R~

Featured image: Bombom was old and tired, ready for his final walk to the temple.